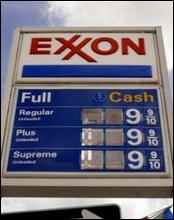

High Oil Prices Met with Anger Worldwide

High Oil Prices Met with Anger Worldwide

By Paul Blustein and Craig Timberg

The Washington Post

Monday 03 October 2005

Both rich and poor countries make moves to appease citizens.

Rising fuel prices are stoking popular anger around the world, throwing politicians on the defensive and forcing governments to resort to price freezes, tax cuts and other measures to soothe voter resentment.

The latest example came this weekend in Nigeria, where President Olusegun Obasanjo promised in a nationally televised Independence Day speech that the cost of gasoline would not increase further until the end of 2006, no matter what happened in global oil markets. He acted after furious demonstrations shut down whole sections of major cities around the country over the past several weeks.

Antagonism over the strains inflicted by escalating energy costs is a phenomenon that stretches from rich nations in Western Europe, where filling up a minivan costs upward of $100, to poor countries in Asia and Africa, where rising oil prices have driven up the cost of bus rides and kerosene used for cooking.

Although prices vary widely around the globe, with many governments keeping fuel costs below market levels and others maintaining stiff taxes on petroleum products, the mood in many parts of the world can be summed up in the lamentations of Julia Seitsang, a mother of 10 who lives in Windhoek, the capital of the southern African country of Namibia.

"Gas prices are biting us so hard it stings," said Seitsang, a 46-year-old businesswoman, opening her wallet to show just a few Namibian coins as she stood on a busy street looking for someone to share a taxi. "I have to spend more and more for my husband to drive my children to school every day."

Adding that her children, who go to three different schools according to their grades and talents, might have to be moved to one school because of the family's gasoline bill, she said, "I swear we are living in the hands of Jesus with these gas prices."

The impact is particularly hard on people in nations like Namibia, where the average annual income is $5,000 and gas costs about $5 a gallon. They have watched helplessly as the prices of crude oil and petroleum products, which are set in global markets, have soared over the past two years, first because of the powerful demand generated in large part by China's rapidly growing economy and more recently because of the gasoline shortages generated by Hurricane Katrina. But in many wealthy countries as well, discontent among ordinary citizens is compelling politicians to respond.

In the European Union, there was a brief attempt by the 25 member governments to maintain a united front against consumer demands for tax cuts, rebates and other subsidies to offset rising fuel prices. Many of those governments depend on taxes that add as much as $5 to a gallon of gas.

But the unity cracked last month as Poland and Hungary approved fuel tax cuts and Belgium promised a rebate on home heating fuel taxes. In France, where a gallon of regular unleaded gasoline fetches up to $6.81 in Paris, thousands of farmers and truck drivers staged brief street demonstrations two weeks ago, and the government offered them a $36 million package of gas tax breaks and rebates.

In Canada, too, the government, facing an election next year, is scrambling to put together a package to present to the cabinet this week, including a new agency to monitor gas prices, help for low-income Canadians with their home heating bills, and new powers to investigate price-fixing complaints.

Canadians paid about $4.07 per gallon for gasoline shortly after Hurricane Katrina hit, reflecting the surge in petroleum prices for an industry closely tied to the giant U.S. market and taxes that are generally double those in the United States. Although the pump price subsided to an average of $3.50 a gallon last week, "there is a great deal of consumer frustration and outrage," said Cathy Hay, a senior associate at M.J. Ervin & Associates, an independent gas consulting firm in Calgary, Alberta. "It is hard for the average consumer to translate a refinery closed in Texas or Louisiana with how much they pay at a pump in Alberta."

In such countries, where stiff gas taxes help induce motorists to drive small, fuel-efficient cars, the griping by Americans about high gasoline prices evokes little sympathy. Ruth Bridger, a spokeswoman for the AA Motoring Trust, a British consumer advocacy group, said Britons look at the sport-utility vehicles that dominate U.S. highways and think, "Serves you right."

But prices in the United States have risen much faster than those in many parts of the developing world. Governments in developing countries often keep artificial lids on fuel costs - sometimes by making state-owned refineries sell at a loss and using taxpayer funds to keep the refineries running, in other cases by using taxpayer funds to buy imported gasoline.

Therein lies one of the great ironies of the popular revolts against higher energy costs in nations such as Nigeria.

"The fact is, higher oil prices are not being fully passed through to the retail level in many countries," said Mohsin S. Khan, the director of the Middle East and Central Asia Department at the International Monetary Fund. "In the States, higher oil passes through to retail prices very quickly." But in the developing world, Khan said, "virtually everywhere, consumers are being protected in many ways, with governments absorbing the cost in their budgets. There is some pass-through, but it's not complete."

Such subsidies are by no means confined to big oil-exporting countries, like Venezuela and Iran, where gasoline prices are famously cheap, in the tens of cents per gallon.

In India, which imports about 75 percent of its crude oil, domestic fuel prices have risen less than one-third as fast as international prices, according to Hans Timmer, an economist at the World Bank; the government's failure to implement a system of market-determined prices caused state-owned refineries to lose $4.6 billion in 2004.

Next door in Pakistan, despite increases of 4.9 to 8.9 percent in September, fuel prices are still more than 15 percent under world market levels, Timmer said. Many sub-Saharan African governments have been unable to continue the budgetary cost of providing gasoline cheaply, so some have allowed prices to rise at least partially. But not all have; the Central African Republic has frozen prices at the pump since 1999.

Indonesians have been paying about 90 cents a gallon for gasoline - until this weekend, that is, when the government of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono announced that gasoline prices would nearly double and kerosene prices would triple. Officials said they had no choice, since fuel subsidies have swelled to about one-third of government spending. Word of the impending price hike sparked protests in many cities; on Friday, police were using tear gas to disperse thousands of demonstrators. The reaction was muted compared with the deadly rioting triggered by previous price hikes, but the government is bracing for possible violence as the impact sinks in.

Although the relatively restrained level of fuel prices in those countries has helped keep consumers spending and economies growing, the subsidies are imposing a severe burden on taxpayers and cannot continue without bankrupting some of the governments involved, economists contend. "These economies may be delaying a necessary adjustment to high oil prices," said Haruhiko Kuroda, the president of the Asian Development Bank, a Manila-based institution owned by 64 governments. He said the artificially low cost of energy translates into excessive consumption.

But it is not easy for governments to shed subsidies, because citizens get upset when the price goes up, whether it is subsidized or not.

Zhang Qihe, 43, a Beijing taxi driver, has seen gas rise from about 91 cents a gallon in 1999 to about $2.30 a gallon now. As a result, he estimates he has to work an extra hour a day to make ends meet. "After a 14-hour workday, I go home exhausted," he complained.

Likewise, in Russia, although major retailers froze prices at the pump this month until the beginning of 2006, that has done little to placate motorists who are paying the equivalent of about $2.60 a gallon, a jump of approximately 20 percent from the beginning of the year.

"The country rakes in oil. We have more oil than anyone," said Nikolai Podkopayev, 45, who drives a van in Moscow delivering car parts. "The government is just not thinking about the people."

Nigeria, a major oil producer, offers perhaps the most disturbing illustration of the depth of antipathy that can arise when fuel costs increase. In Nigeria, rising petroleum prices have dramatically fattened the budgets of the government and the bottom lines of oil businesses but caused a powerful backlash against President Obasanjo and, say some motorists, against democracy itself.

Since Obasanjo's election in 1999 heralded the end of military rule, he has overseen years of steady decreases in government fuel subsidies at the urging of the World Bank. Prices have increased 44 percent, up to $1.74 per gallon, in just the past two months - a bargain to Americans, perhaps, but not to impoverished Nigerians.

Many motorists have taken to filling up tanks only partway, a few dollars at a time, as money becomes available. Mohammed Ali, 26, a government contractor, said it costs $25 to fill the tank of his black Honda coupe. On this afternoon, he put about $3.50 worth in the tank.

"It's a really big problem," Ali said. "Since we are one of the oil-producing nations, the pump risings should be affordable."

In the spate of protests that has recently erupted, the most vehement participants have been motorcycle taxi drivers, generally recent migrants from poor, rural areas who have few job prospects. They say that ridership has fallen as they have been forced to raise their prices.

Mohammed Sani, 28, said he can recall that gas prices were one-sixth the price they are now under military dictator Sani Abacha in the 1990s. He said he would welcome a return to military rule if gas prices returned to those levels.

"We are not happy with democracy," Sani said. "All our eyes are on petroleum" prices.

A gas station manager, Zamani Maisamari, 30, said the public anger comes from the combination of higher prices, a weak job market and stagnating services. Heavy fuel subsidies, he said, were one of the few forms of government spending that ordinary Nigerians could feel.

"You go to the hospital, there are no drugs," he said. "You go on the roads, they are not good."

He added, "Ever since we experienced democracy, each year it's increasing price, price, price. Year after year."

-------

Link Here

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home