Uncomfortably Numb to Torture

By JoAnn Wypijewski The Los Angeles Times

Saturday 30 September 2006

As America's politicians, media and citizens get used to wartime abuses, Bush's horrific policies get a pass.

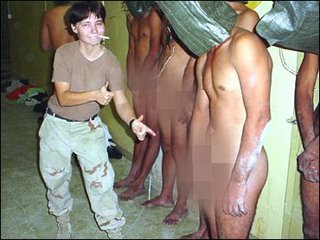

A year ago this week, a military jury convicted Army Reserve Pfc. Lynndie R. England of maltreating detainees. The face of the Abu Ghraib scandal, England is forever fixed in photographs as the girl with the bowl cut and the pixie smile who pointed at Iraqi prisoners while they were forced to masturbate and who held a writhing, naked man by a leash. Before sentencing, the Army prosecutor thundered: "Who can think of a person who has disgraced this uniform more? Who has held the US military up for more dishonor?"

Indeed, it was that uniform - not the breach of immutable standards of decency held by this nation - that put England in the dock and eventually in prison. It was that uniform and nothing else, because if England and the others charged in the scandal had been civilian interrogators instead of military police, they would be among the privileged torturers whom President Bush and members of both parties in Congress are determined to keep on the job and to shield from future prosecution.

Abu Ghraib has become shorthand for the kind of abhorrent behavior that, in the latest discussion about interrogation techniques, nobody ventures to allow. In that sense, Abu Ghraib is the new American standard, a negative one, marking the line that must not be crossed. A positive standard - that is, humane treatment of unarmed prisoners - being inconceivable, debate turns on permissible degrees of inhumanity; "rough stuff," as New York Times columnist David Brooks and others justifying pain say lightly.

So here is the bitter joke: England, the public emblem of torture, was convicted for nothing so awful as what the president and his flank have chosen to protect. Her crime was to smile, to pose, to jeer at naked, powerless men, and to fail to stop their humiliations or to report them afterward. She did not shackle men in stress positions, strip them of their clothes, deny them sleep, force them to stand for hours or days, douse them with icy water, deprive them of heat or food or subject them to incessant noise or screaming.

Despite Arizona Republican Sen. John McCain's compromise, none of those brutalities is expressly outlawed in the legislation that Congress just passed and the president is about to sign.

Such brutalities were regular fare at Abu Ghraib because interrogation, by civilian and military personnel, was regular fare. But interrogation was largely sidestepped in the Abu Ghraib trials, in which prosecutors focused on what soldiers did for "fun," for "laughs," with common criminals "of no value" to US intelligence. The infamous pyramid and sexual mortifications were not part of interrogations, so these formed the centerpiece of criminal charges. The daily application of fear and cold and want and pain - what Spc. Charles A. Graner Jr., the putative ringleader of the scandal at Abu Ghraib, called his job of "terrorizing prisoners" - was an accompaniment to questioning, so it went unpunished.

"We just humiliated them," England said; it could have been worse. For many detainees, it was. Two days before England was photographed laughing at prisoners, Manadel Jamadi died in a shower stall at Abu Ghraib. Army investigators found that he entered the stall under his own power with civilian interrogators said to be from the CIA. Later, soldiers smiled in pictures with his corpse. The interrogators had vanished, and no one was charged.

Congress would never justify murder by interrogators, but it hasn't insisted that anyone be held accountable for Jamadi's death either. There's a similar indifference to accountability in the one case in the Abu Ghraib scandal unavoidably linked to interrogation.

The Army never took a sworn statement from the prisoner who was forced to stand atop a box, draped in a hood and cape and told he would get a shock if he moved. Then the Army conveniently lost him, and though the MPs who improvised his ghoulish torment went to prison, the civilian interrogator who the MPs said instructed them to keep the prisoner awake was never charged. Take away the bogus wires and the iconic costume and this is the kind of treatment the president says is absolutely necessary for our safety.

The bold opposition wags a finger but leaves it to the president to set the rules. Where is the outrage? Like England and the others who went from good to bad, or bad to worse, through acquaintance with cruelty, finally accommodating themselves to it or even administering it, the citizenry, the media and the politicians have become insensible to horror.

Years of conditioning to abuse and war have had a numbing effect. So the president's advocacy of an "alternate set of procedures" for detainees gets a pass. The Democrats' official response, a pass. The McCain compromise, a pass masquerading as courageous dissent. Public reaction to legislating indefinite detention, the admissibility of hearsay, prosecutions based on torture, a pass.

As at Abu Ghraib, up is down, day is night.

JoAnn Wypijewski covered the Abu Ghraib trials at Ft. Hood, Texas, for Harper's magazine.

The Circle of Life

Naomi Klein had a very interesting commentary (“Children of Bush’s America: The torturers of Abu Ghraib were McWorkers who ended up in Iraq because they could no longer find decent jobs at home”) in the Guardian of London this week. (One difference between commentaries in English papers and those in American papers is that the English ones deal with facts. Come to think of it, that’s one difference between commentaries in English papers and news stories in American ones.) Examining the factors that came together to create the American prison at Abu Ghraib, Klein writes:

More than 82% of the jobs created [in the United States] in April were in service industries, including restaurants and retail. The biggest new employers were temp agencies. Over the past year, 272,000 manufacturing jobs have been lost. No wonder the president’s economic report in February floated the idea of reclassifying fast-food restaurants as factories. “When a fast-food restaurant sells a hamburger, for example, is it providing a ‘service’ or is it combining inputs to ‘manufacture’ a product?” the report asks.

But not all of the job growth in the US has come from burger-flipping and temping. With more than 2 million Americans behind bars, the number of prison guards has exploded - from 270,317 in 2000 to 476,000 in 2002.

The ridiculous remark about the possibility of reclassifying fast-food restaurants as factories (and a further one: “Mixing water and concentrate to produce soft drinks is classified as manufacturing. However, if that activity is performed at a snack bar, it is considered a service”) comes from the same February report about which Gregory Mankiw, the President’s top economic advisor, stated: “Outsourcing is just a new way of doing international trade. More things are tradable than were tradable in the past and that’s a good thing.”

Since George Bush became President, we’ve been blessed with an overabundance of good things—over 2.7 million manufacturing jobs have been lost. Unemployment in manufacturing cities such as Rockford is over ten percent. Setting aside the question of how much of this can be laid at the feet of the current administration and how much is the result of the free-trade policies of the Bush I and Clinton administrations, there is no doubt that the loss of manufacturing jobs has been a political hot potato for George W. Bush—and a boon for military recruitment.

Klein continues:

Free trade has turned the US labour market into an hourglass: plenty of jobs at the bottom, a fair bit at the top, but very little in the middle. At the same time, getting from the bottom to the top has become increasingly difficult, with tuition fees at state colleges up by more than 50% since 1990.

That has led many—among them, Jessica Lynch, Lynddie England, and England’s fellow Abu Ghraib guard Sabrina Harman—to sign up for a tour of duty, in the promise of receiving college tuition after four years (a phenomenon Klein call the “Nafta draft”). Their dire economic straits do not excuse their actions, but they do help to explain why people who were unsuited for duty ended up in the military. (This does not explain, however, why they were accepted into the service.)

Of course, the poverty of the soldiers involved in prison torture makes them neither more guilty, nor less. But the more we learn about them, the clearer it becomes that the lack of good jobs and social equality in the US is precisely what brought them to Iraq in the first place.

Despite his attempts to use the economy to distract attention from Iraq, and his efforts to isolate the soldiers as un-American deviants, these are the children George Bush left behind, fleeing dead-end McJobs, abusive prisons, unaffordable education and closed factories.

It’s a powerful article and a good counterweight to the libertarian argument (advanced today by Gene Callahan) that Abu Ghraib simply stems from “the nature of the State.” Yes, indeed, the state has played an important role here, not least in instituting the free-trade agreements that have led to the outsourcing that Callahan and his LewRockwell.com colleagues cannot praise enough. And the state has played no small part in the cultural corruption so well documented by Tom Fleming in “The Face of America”. But to get so wrapped up in a theory that you blame Abu Ghraib on the “nature of the State” and ignore the increasing cultural decadence and economic decline in which we find ourselves is to willingly blind yourself to reality.

I don’t like this war, or the way it has been conducted, any more than does Callahan. The answer to our problems, however, does not lie in some pie-in-the-sky theory about the glory days that will ensue after the (never-to-be-consummated) destruction of the state but, instead, in opening our eyes to the ways in which the political, economic, and cultural decline of America continue to reinforce one another.

(By the way, the Guardian, while clearly rooting for John Kerry, has had some of the best and most in-depth coverage of the U.S. presidential election so far, particularly the ongoing series by Matthew Wells, who is traveling through the Midwest, covering reactions to the war and its possible effect on the election. You can find his first three articles here, here, and here.)

Link Here

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home