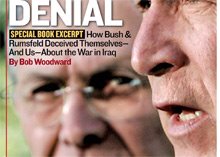

Excerpt: State of Denial by Bob Woodward

Interesting Huh, Who was sitting with Bush Senior on the night of 9/11.

Chapter One

In the fall of 1997, former President George H. W. Bush, then age 74 and five years out of the White House, phoned one of his closest friends, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the longtime Saudi Arabian ambassador to the United States.

"Bandar," Bush said, "W. would like to talk to you if you have time. Can you come by and talk to him?" His eldest son and namesake, George W. Bush, who had been governor of Texas for nearly three years, was consulting a handful of people about an important decision and wanted to have a private talk.

Bandar's life was built around such private talks. He didn't ask why, though there had been ample media speculation that W. was thinking of running for president. Bandar, 49, had been the Saudi ambassador for 15 years, and had an extraordinary position in Washington. His intensity and networking were probably matched only by former President Bush.

They had built a bond in the 1980s. Bush, the vice president living in the shadow of President Ronald Reagan, was widely dismissed as weak and a wimp, but Bandar treated him with the respect, attention and seriousness due a future president. He gave a big party for Bush at his palatial estate overlooking the Potomac River with singer Roberta Flack providing the entertainment, and went fishing with him at Bush's vacation home in Kennebunkport, Maine -- Bandar's least favorite pastime but something Bush loved. The essence of their relationship was constant contact, by phone and in person.

Like good intelligence officers -- Bush had been CIA director and Bandar had close ties to the world's important spy services -- they had recruited each other. The friendship was both useful and genuine, and the utility and authenticity reinforced each other. During Bush's 1991 Gulf War to oust Saddam Hussein from Kuwait and prevent him from invading neighboring Saudi Arabia, Bandar had been virtually a member of the Bush war cabinet.

At about 4 A.M. on election day 1992, when it looked as if Bush was going to fail in his bid for a second term, Bandar had dispatched a private letter to him saying, You're my friend for life. You saved our country. I feel like one of your family, you are like one of our own. And you know what, Mr. President? You win either way. You should win. You deserve to. But if you lose, you are in good company with Winston Churchill, who won the war and lost the election.

Bush called Bandar later that day, about 1 P.M., and said, "Buddy, all day the only good news I've had was your letter." About 12 hours later, in the early hours of the day after the election, Bush called again and said, "It's over."

Bandar became Bush's case officer, rescuing him from his cocoon of near depression. He was the first to visit Bush at Kennebunkport as a guest after he left the White House, and later visited him there twice more. He flew friends in from England to see Bush in Houston. In January 1993 he took Bush to his 32-room mansion in Aspen, Colorado. When the ex-president walked in he found a "Desert Storm Corner," named after the U.S.-led military operation in the Gulf War. Bush's picture was in the middle. Bandar played tennis and other sports with Bush, anything to keep the former president engaged.

Profane, ruthless, smooth, Bandar was almost a fifth estate in Washington, working the political and media circles attentively and obsessively. But as ambassador his chief focus was the presidency, whoever held it, ensuring the door was open for Saudi Arabia, which had the world's largest oil reserves but did not have a powerful military in the volatile Middle East. When Michael Deaver, one of President Reagan's top White House aides, left the White House to become a lobbyist, First Lady Nancy Reagan, another close Bandar friend, called and asked him to help Deaver. Bandar gave Deaver a $500,000 consulting contract and never saw him again.

Bandar was on hand election night in 1994 when two of Bush's sons, George W. and Jeb, ran for the governorships of Texas and Florida. Bush and former First Lady Barbara Bush thought that Jeb would win in Florida and George W. would lose in Texas. Bandar was astonished as the election results poured in that night to watch Bush sitting there with four pages of names and telephone numbers -- two pages for Texas and two for Florida. Like an experienced Vegas bookie, Bush worked the phones the whole evening, calling, making inquiries and thanking everybody -- collecting and paying. He gave equal time and attention to those who supported the new Texas governor and the failed effort in Florida.

Bandar realized that Bush knew he could collect on all his relationships. It was done with such a light, human touch that it never seemed predatory or grasping. Fred Dutton, an old Kennedy hand in the 1960s and Bandar's Washington lawyer and lobbyist, said that it was the way Old Man Kennedy, the ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, had operated, though Kennedy's style had been anything but light.

Bandar planned his 1997 visit with the Texas governor around a trip to a home football game of his beloved Dallas Cowboys. That would give him "cover," as he called it. He wanted the meeting to be very discreet, and ordered his private jet to stop in Austin.

When they landed, Bandar's chief of staff came running up to say the governor was already there outside the plane. Bandar walked down the aisle to go outside.

"Hi, how are you?" greeted George W. Bush, standing at the door before Bandar could even get off the plane. He was eager to talk.

"Here?" inquired Bandar, expecting they would go to the governor's mansion or office.

"Yes, I prefer it here."

Bandar had been a Saudi fighter pilot for 17 years and was a favorite of King Fahd; his father was the Saudi defense minister, Prince Sultan. Bush had been a jet pilot in the Texas Air National Guard. They had met, but to Bandar, George W. was just another of the former president's four sons, and not the most distinguished one.

"I'm thinking of running for president," said Bush, then 52. He had hardly begun his campaign for reelection as governor of Texas. He had been walking gingerly for months, trying not to dampen his appeal as a potential presidential candidate while not peaking too early, or giving Texas voters the impression he was looking past them.

Bush told Bandar he had clear ideas of what needed to be done with national domestic policy. But, he added, "I don't have the foggiest idea about what I think about international, foreign policy.

"My dad told me before I make up my mind, go and talk to Bandar. One, he's our friend. Our means America, not just the Bush family. Number two, he knows everyone around the world who counts. And number three, he will give you his view on what he sees happening in the world. Maybe he can set up meetings for you with people around the world."

"Governor," Bandar said, "number one, I am humbled you ask me this question." It was a tall order. "Number two," Bandar continued, "are you sure you want to do this?" His father's victory, running as the sitting vice president to succeed the popular Reagan in the 1988 presidential election was one thing, but taking over the White House from President Bill Clinton and the Democrats, who likely would nominate Vice President Al Gore, would be another. Of Clinton, Bandar added, "This president is the real Teflon, not Reagan."

Bush's eyes lit up! It was almost as if the younger George Bush wanted to avenge his father's loss to Clinton. It was an electric moment. Bandar thought it was as if the son was saying, "I want to go after this guy and show who is better."

"All right," Bandar said, getting the message. Bush junior wanted a fight. "What do you want to know?"

Bush said Bandar should pick what was important, so Bandar provided a tour of the world. As the oil-rich Saudi kingdom's ambassador to the United States, he had access to world leaders and was regularly dispatched by King Fahd on secret missions, an international Mr. Fix-It, often on Mission Impossible tasks. He had personal relationships with the leaders of Russia, China, Syria, Great Britain, even Israel. Bandar spoke candidly about leaders in the Middle East, the Far East, Russia, China and Europe. He recounted some of his personal meetings, such as his contacts with Mikhail Gorbachev working on the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan. He spoke of Maggie Thatcher and the current British prime minister, Tony Blair. Bandar described the Saudi role working with the Pope and Reagan to keep the Communists in check. Diplomacy often made strange bedfellows.

"There are people who are your enemies in this country," Bush said, "who also think my dad is your friend."

"So?" asked Bandar, not asking who, though the reference was obviously to supporters of Israel, among others.

Bush said in so many words that the people who didn't want his dad to win in 1992 would also be against him if he ran. They were the same people who didn't like Bandar.

"Can I give you one advice?" Bandar asked.

"What?"

"Mr. Governor, tell me you really want to be president of the United States."

Bush said yes.

"And if you tell me that, I want to tell you one thing: To hell with Saudi Arabia or who likes Saudi Arabia or who doesn't, who likes Bandar or doesn't. Anyone who you think hates your dad or your friend who can be important to make a difference in winning, swallow your pride and make friends of them. And I can help you. I can help you out and complain about you, make sure they understood that, and that will make sure they help you."

Bush recognized the Godfather's advice: Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer. But he seemed uncomfortable and remarked that that wasn't particularly honest.

"Never mind if you really want to be honest," Bandar said. "This is not a confession booth. If you really want to stick to that, just enjoy this term and go do something fun. In the big boys' game, it's cutthroat, it's bloody and it's not pleasant."

Bandar changed the subject. "I was going to tell you something that has nothing to do with international. When I was flying F-102s in Sherman, Texas, Perrin Air Force Base, you were flying F-102s down the road at another Texas base. Our destiny linked us a long time ago by flying, without knowing each other." He said he wanted to suggest another idea.

"What?"

"If you still remember what they taught you in the Air Force. I remember it because I spent 17 years. You only spent a few years. Keep your eye on the ball. When I am flying that jet and my life is on the line, and I pick up that enemy aircraft, I don't care if everything around me dies. I will keep my eye on that aircraft, and I will do whatever it takes. I'll never take my eye off."

Former President Bush continued in his efforts to expand his son's horizons and perhaps recruit future staff.

"George W., as you know, is thinking about what he might want to do," he told Condoleezza Rice, the 43-year-old provost of Stanford and one of his favorite junior National Security Council staffers from his White House years. "He's going to be out at Kennebunkport. You want to come to Kennebunkport for the weekend?"

It was August 1998. The former president was proposing a policy seminar for his son.

Rice had been the senior Russia expert on the NSC, and she had met George W. in a White House receiving line. She had seen him next in 1995, when she had been in Houston for a board meeting of Chevron, on which she served, and Bush senior invited her to Austin, where W. had just been sworn in as governor. She talked with the new governor about family and sports for an hour and then felt like a potted plant as she and the former president sat through a lunch Bush junior had with the Texas House speaker and lieutenant governor.

The Kennebunkport weekend was only one of many Thursday-to-Sunday August getaways at Camp Bush with breakfast, lunch, dinner, fishing, horseshoes and other competitions.

"I don't have any idea about foreign affairs," Governor Bush told Rice. "This isn't what I do."

Rice felt that he was wondering, Should I do this? Or probably, Can I do this? Out on the boat as father and son fished, the younger Bush as

ked her to talk about China, then Russia. His questions flowed all weekend -- what about this country, this leader, this issue, what might it mean, and what was the angle for U.S. policy.

ked her to talk about China, then Russia. His questions flowed all weekend -- what about this country, this leader, this issue, what might it mean, and what was the angle for U.S. policy.Early the next year, after he was reelected Texas governor and before he formally announced his presidential candidacy, Rice was summoned to Austin again. She was about to step down as Stanford provost and was thinking of taking a year off or going into investment banking for a couple of years.

"I want you to run my foreign policy for me," Bush said. She should recruit a team of experts.

"Well, that would be interesting," Rice said, and accepted. It was a sure shot at a top foreign policy post if he were to win.

LinkHere

The Secret Relationship Between the World's Two Most Powerful Dynasties

Salon.com -- By Craig Unger Immediately after 9/11, dozens of Saudi royals and members of the bin Laden family fled the U.S. in a secret airlift authorized by the Bush White House. One passenger was an alleged al-Qaida go-between, who may have known about the terror attacks in advance. Our first excerpt from "House of Bush, House of Saud." Editor's note: President Bush is campaigning for reelection as the Western world's leader in the war against terrorism. But the president's family has long been closely tied -- through a complex web of oil, money and power -- to the royal family of Saudi Arabia, which has maintained its despotic grip on the petroleum-rich kingdom through an alliance with the most militant strain of Islamic fundamentalism. Journalist Craig Unger has been covering the alliance between the Bush family and the House of Saud for years. His reporting raises crucial questions about the consequences of this personal, political and financial partnership for U.S. foreign policy, democracy and the future of the world. Salon is proud to present a series of excerpts from Unger's book "House of Bush, House of Saud," to be published on March 16 by Scribner. >>>>cont

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home