The Big Stall: How Bush gamed the media to get re-elected in 2004

The Big Stall: How Bush gamed the media to get re-elected in 2004

Link Here"Nothing gave us more trouble during my years on [the paper] than the conflict with the government over what should and should not be published during periods of war or threats of war."

-- James Reston, New York Times columnist, in his autobiography, "Deadline."

Forty-four years later, the New York Times is still trying to get it right. In 1961, the Kennedy Administration talked the Times into spiking an article that would have prevented the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion, the trigger for a series of unfortunate events that stretched to Watergate and, according to H.R. Haldeman, JFK's assassination.

Now, the Times -- again, at the request of the White House -- has held onto a national security bombshell: President Bush's unlawful authorization of domestic spying on international phone calls and emails of hundreds and possibly thousands of people inside the U.S.

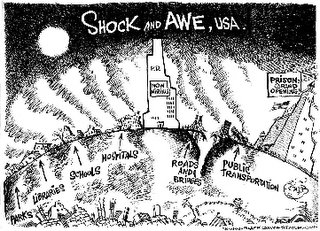

The story in and of itself is a shocker, even as it comes right after the NBC report that an obscure Pentagon agency has monitored the activities of peaceful anti-war protestors. It's too early to gauge reaction, but we expect that it will be highly negative, not just from the usual suspects on the left but also from the vast political middle -- the heartland types who just barely propelled Bush to re-election in 2004.

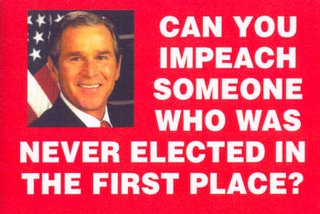

And there lies the real story behind the story. Because it appears it may have been possible for the Times to publish at least some of the details of the Bush-ordered domestic spying before Nov. 2, 2004, the day that the president nailed down four more years. Although Bush won by 2 percent nationally, a switch of just 59,302 Ohio voters from Bush to John Kerry would would have put the Democrats back in the White House.

Would Bush won the election if the extent of his seemingly unconstitutional domestic spying had been known? We'll never know. For roughly a year, the White House successfully leaned on the Times to keep the story under wraps. It's not known when the Bush lobbying of the Times began. But it is clear that the warning signs about the program -- the alarm bells that likely triggered the Times investigation in the first place -- were going off by mid-2004, months before the vote.

Here's the money shot from today's Times article:

The White House asked The New York Times not to publish this article, arguing that it could jeopardize continuing investigations and alert would-be terrorists that they might be under scrutiny. After meeting with senior administration officials to hear their concerns, the newspaper delayed publication for a year to conduct additional reporting. Some information that administration officials argued could be useful to terrorists has been omitted.

We'd like to know a lot more about how this all transpired -- who talked to whom at the Times, and when did they talk? Did the pleading come before Nov. 2, 2004, or after? Was anyone on the White House political side -- i.e., Karl Rove --involved? You would think that after the Judy Miller fiasco, the Times would be much, much more transparent in the backstory of how this story was published. But you would think wrong.

It's not clear what good came of holding the story for so long. The major arrest cited by administration officials -- "Iyman Faris, an Ohio trucker and naturalized citizen who pleaded guilty in 2003 to supporting Al Qaeda by planning to bring down the Brooklyn Bridge with blowtorches," a plan that was ridiculed by some -- took place in 2003.

The story notes that "most people targeted for N.S.A. monitoring have never been charged with a crime, including an Iranian-American doctor in the South who came under suspicion because of what one official described as dubious ties to Osama bin Laden."

More importantly, holding the story doesn't make a lot of sense because the problems with Bush's order were so apparent to the key sources by mid-2004 that that program had been substantially altered, anyway. The article notes:

In mid-2004, concerns about the program expressed by national security officials, government lawyers and a judge prompted the Bush administration to suspend elements of the program and revamp it.

This is the unfortunate collision of two related trends. One, which has been much discussed in recent months, was the major dive taken by the mainstream media after the 9/11 attacks, the subject of a recent book called "Feet to the Fire: The Media After 9/11," edited by Kristen Borjesson. As Helen Thomas notes in the book:

"From 9/11, the American press suddenly had to be the superpatriots. The press went into a coma."

The executive editor of the New York Times, Bill Keller, was no exception. As we wrote recently, Keller's thinking on the invasion of Iraq in mid-2003 was shaped in one-on-one meetings with Bush neocon Iraq hawk Paul Wolfowitz, who assured the Times editor that Saddam Hussein "was hiding something" even as he told other reporters that WMD in Iraq was merely "the one issue that everyone could agree on" for a pre-determined invasion.

The result of the Times' deference to authority was Judy "Miss Run Amok" Miller's much maligned coverage of the weapons in Iraq that proved not to be there.

But something else was going on in 2004 in addition to the 9/11 hangover. It's now clear that the Bush White House was waging war on a series of fronts, with differing tactics, to postpone some inevitable bad news until after the 2004 election. They were counting on timidity from the press, and they got what they were seeking. For example:

The Valerie Plame affair. Media Matters for America nailed down the press's cowardice in dealing with the issues in this case during the heat of the 2004 campaign season...

During his October 28 press conference following the indictment of I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby for perjury, obstruction of justice, and false statements, special counsel Patrick J. Fitzgerald noted that, had witnesses testified "when the subpoenas were issued in August 2004," indictments would have come "in October 2004 instead of October 2005."

Fitzgerald's mention of subpoenas issued in August 2004 is a clear reference to New York Times reporter Judith Miller, who was subpoenaed that month but didn't testify until October 2005, after spending 85 days in jail for violating a court order instructing her to testify. In referring to "witnesses," Fitzgerald also seems to have had Time magazine reporter Matthew Cooper in mind. Cooper was subpoenaed in May 2004 but was held in contempt in August 2004 and refused to testify until July 2005....

An August 25 Los Angeles Times article appears to be the first mention in the media that Cooper's failure to reach out to Rove before the election reflected a view at Time that the magazine should avoid involvement in the issue before the election: "Cooper did not ask Rove for a waiver, in part because his lawyer advised against it. In addition, Time editors were concerned about becoming part of such an explosive story in an election year.

But White House maipulation played a role:, as E.J. Dionne noted:

Libby, the good soldier, pursued a brilliant strategy to slow the inquiry down. As long as he was claiming that journalists were responsible for spreading around the name and past CIA employment of Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, Libby knew that at least some news organizations would resist having reporters testify. The journalistic "shield" was converted into a shield for the Bush administration's coverup.

Then, of course, there's the case of Dan Rather, Bush's National Guard service, and the likely forged memos. We won't get into the conspiracy theories, but it's clear that the right-wing pushback after this whole fiasco basically neutralized CBS News for the rest of the 2004 campaign, as well as preventing others from pursuing Bush's Guard service. Does anyone else remember this?

(AP) CBS News has shelved a "60 Minutes" report on the rationale for war in Iraq because it would be "inappropriate" to air it so close to the presidential election, the network said on Saturday.

The report on weapons of mass destruction was set to air on Sept. 8 but was put off in favor of a story on President Bush's National Guard service. The Guard story was discredited because it relied on documents impugning Bush's service that were apparently fake.

CBS News spokeswoman Kelli Edwards would not elaborate on why the timing of the Iraq report was considered inappropriate.

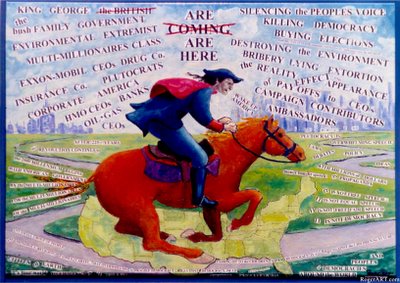

Simply put, the Bush White House gamed the media in 2004. They used every trick in their playbook: Manipulating the comatose post-9/11 media and its gullible trust in authority, playing on kneejerk protection of sources, and when that failed, either resorting to bullying (as in the case of CBS) or pleading national security on barely defendable grounds.

And we fell for it, big time. Voters could have gone to the polls on Election Day, Nov. 4, 2004, knowing that Bush was spying on Americans, that a key White House aide was charged with felonies, and that the initial rationales for Iraq were bogus.

And so it turns out that the media had the power to alter this country's disastrous direction back in 2004, after all. And we didn't even have to click our heels three times.

We'd only needed to do our job.

UPDATE: Times editor Bill Keller has issued a statement, and you can read it here at Salon (non-members -- i.e., most people -- must watch an ad first). It's not too satisfactory, though. It seems to sidestep the timing issue. Also, this line about the initial decision to hold the story jumped out at us:

Officials also assured senior editors of the Times that a variety of legal checks had been imposed that satisfied everyone involved that the program raised no legal questions.

It's that easy, huh?

Question? How the friking Hell, can you give Iraq Democracy when there is no Bloody Democracy in America today.

Question? How the friking Hell, can you give Iraq Democracy when there is no Bloody Democracy in America today.

Washington Post Jonathan Weisman December 16, 2005 at 11:18 AM

Washington Post Jonathan Weisman December 16, 2005 at 11:18 AM