By Lizette Alvarez

The New York Times

Friday 07 April 2006

After Neil Santorello heard the news that his son, a tank commander, had been killed in Iraq, from the officer in his living room, he walked out his front door and removed the American flag from its pole. Then, in tears, he tore down the yellow ribbons from his tree.

Rather than see it as the act of a man unmoored by the death of his 24-year-old son, the officer, an Army major, confronted Mr. Santorello, saying,

"Don't be disrespectful," Mr. Santorello recalled. Then, the officer, whose job it is to inform families of their loss, quickly disappeared without offering any comfort.

Later, the Santorellos heard a piece of crushing but inaccurate news: They would not be allowed to look inside their son's coffin. First Lt. Neil Santorello, of Verona, Pa., had been killed by an improvised bomb. His body, the family was told, was unviewable.

The Santorellos eventually learned that families have the right to see a loved one's body.

"I asked them to open the casket a few inches so I could reach in and touch his hand," recalled Mr. Santorello, who is still struggling with his son's death, in large part because he was not allowed to see him.

"The government doesn't want you to see servicemen in a casket, but this is my son. He is not a serviceman. You have to let his mother and I say goodbye to him."

Scores of families whose loved ones have died fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan have gone head-to-head with a casualty system that, in their experience, has failed to compassionately and competently guide them through the harrowing process that begins after a soldier's death.

When the system works smoothly, and it often does, families say they feel a profound sense of comfort. But others have seen their hurt deepen.

They have complained about coffins placed in cargo bays alongside crates, personal belongings that disappear, questions about how their loved ones died that go unanswered for months or even years, and casualty assistants who are too poorly trained to walk them through the labyrinth of their anguish.

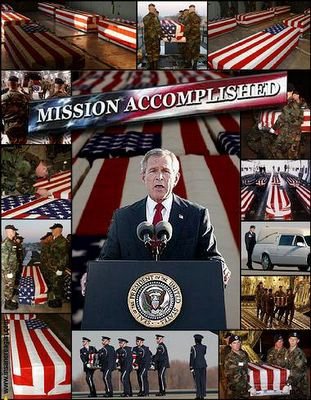

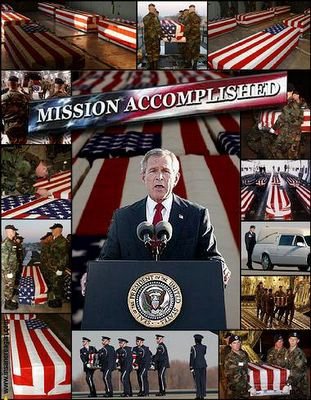

After three years of war in Iraq, with the number of active-duty deaths there surpassing 2,330, the military is scrambling to improve the way it cares for surviving relatives and honors soldiers who have been killed in battle. Even senior officials, including the secretary of the Army, have acknowledged flaws in the system.

Not since the Vietnam War have so many service members in dress uniforms knocked on so many doors to deliver such somber news.

The Army, which has suffered the largest number of deaths, 1,589 as of March 28, has faced an enormous challenge and has received the sharpest criticism for its treatment of surviving families and soldiers killed in action.

Now it is rushing through new regulations to overhaul the casualty process, which has been tinkered with, but not fully revised, since 1994. "We take it to heart whenever something is not done properly and are painfully aware of the additional grief it brings to the family concerned," said Col. Mary Torgersen, the director of the Army's Casualty and Memorial Affairs Operation Center, in an e-mail response to questions, adding that some changes have already been put in place.

For some grieving families, the cracks in the system have deepened their distress and many have been turned to Congress, state officials and private lawyers for help.

Many wonder why it has taken the military so long to address their concerns. The answer appears straightforward: The military did not expect to be fighting this long. It also did not expect to lose this many soldiers.

Lapses in the past few years run from the heart-wrenching to the head-scratching. Families have said that items like cameras and computers containing treasured e-mail messages and photographs have been lost or damaged.

Gay and Fred Eisenhauer, of Pinckneyville, Ill., whose son, Wyatt, an Army scout, was killed last May in Iraq by an improvised bomb, are still hoping to receive their son's watch, eyeglasses and cellphone. The phone is precious because it holds a recording of their son's voice. A combat patch they were promised has never arrived.

"I know these are little things," Mrs. Eisenhauer said. "What makes it important to me is that my son was good enough to go over there to fight, but he is not important enough to get his stuff back to his family."

Colonel Torgersen said the Casualty and Memorial Affairs Operation Center "aggressively monitors the movement" of personal effects. Mortuary specialists inventory, photograph, clean and then ship belongings to the center via Federal Express.

Soldiers, in their coffins, usually arrive from Dover Air Force Base in the belly of a commercial flight. But honor guards have not always been present as the coffins come off the plane.

The Eisenhauers had hoped to take comfort in the military rituals. Instead, the airline placed Private Eisenhauer's coffin in a cargo warehouse with crates and boxes stacked high around it. There was no ceremony, no flag over the coffin.

Only the airport firefighters did their bit to honor him, hoisting flags on their ladder trucks.

"I just wanted to scream," Mrs. Eisenhauer said. "My son was owed that. He was owed that."

When Joan Neal of Gurnee, Ill., went to the airport for the body of her son, Specialist Wesley Wells, 21, she was aghast. "To glance over and see your child's casket on a forklift is not really the kind of thing you want to see," Ms. Neal said.

News of a death has also been delivered at awkward times. Ms. Neal was at work when she was notified in September 2004 that her son had been killed in Afghanistan, and Mrs. Eisenhauer's 6-year-old niece was in the room when Mrs. Eisenhauer received the news.

As parents to a married son, the Santorellos experienced something that is commonplace: The Army focuses on the spouse and has often left parents to fend for themselves.

The Santorellos were not assigneda casualty assistant and were expected to pay their own way to a memorial ceremony in Fort Riley, Kan., and to find transportation to the burial at Arlington Cemetery.

"We were not considered next of kin," said Mr. Santorello, who with his wife, Dianne, opposes the war. "He was my son for 25 years. He was her husband for 22 months, and I had no say."

Recognizing the distress of parents with married children, the Army in mid-February began assigning casualty assistants to mothers and fathers.

Unanswered Questions

Some families say that the most upsetting aspect of the casualty process may be the lack of information about how the loved ones died.

In a 2005 survey of 50 military families by The Military Times, about half of the families said they did not know enough about their loved ones' deaths.

Parents and spouses crave details to help them cope, particularly because they cannot visit the spot where loved ones died: Who held his hand? Did he say anything?

"You know what my casualty assistant said? 'These are just questions you will never get answers to,'" Ms. Eisenhauer said. "But there were men there. Why can't I get answers?"

The Santorellos were told by the Army that their son had died instantly. A few weeks later, they received a letter saying he had lived for four hours.

Mrs. Santorello learned the time of death by reading the autopsy report. "I don't think anyone should be forced to read an autopsy report to find out when their son died," she said.

Ms. Neal's casualty officer told her that her son had been killed in action by a gunshot wound to the chest. After her son's funeral, Ms. Neal learned that he might have been killed by his own forces.

She had been told that she would be notified in 30 days. Seven months later, when she still had not received further news, she took a plane to Hawaii, where her son had been stationed, to talk with his superiors, who greeted her warmly.

"They did confirm he was killed by American bullets," she said. "The autopsy was done within a week of his death. They knew that when they did the autopsy."

A Personal Apology

Karen Meredith's son Lt. Ken Ballard, 26, a fourth-generation Army officer and a tank commander, was killed in Iraq in May 2004.

Her experience went so awry that she received a personal letter of apology last September from the secretary of the Army, Francis J. Harvey.

The problems began when her casualty officer abandoned her after 10 days, just as the process was beginning. It also took five months to receive Lieutenant Ballard's personal belongings. His clothes were returned washed, which might have made some families thankful, but devastated her. But there was worse to come.

The week her son died, Ms. Meredith was told that he had been killed by enemy fire.

Fifteen months later, there was a knock on the door. Ms. Meredith was told by an Army casualty official that her son's death had been accidental. Her son had been killed when his tank backed into a tree branch, setting off an unmanned machine gun.

"It was not a secret," said Ms. Meredith, now an outspoken critic of the war. "It was incompetence."

"The subliminal assumption is that they take care of everything," added Ms. Meredith, who credits the Army for responding to her complaints and working to fix the system. "They don't. I was tenacious."

Even when soldiers are alive, it can be difficult to get answers. Laura Youngblood, 27, was seven months pregnant with their second child in New York last July when her husband was wounded by an improvised bomb in Iraq.

Because of the pregnancy, she said, the corpsman assisting her did not want to tell her that her husband was "very seriously injured." When she was finally told he was off his ventilator, she recalls saying, "Good, because you never told me he was on one."

Six days after being wounded, he died.

A Sensitive Duty

Many casualty assistants say they recognize the sensitive nature of their task and are assiduous about getting it right. Although all services have different casualty policies. The Marines, steeped in tradition, have been mostly praised for the way they handle the jobs. But all agreed that the job of a casualty assistant is a difficult one. At times, they have become the focus of a family's anger. Sometimes they suffer emotionally, watching as wives crumble or children hysterically cry "Daddy."

Afterward, some casualty assistants seek counseling.

"It's hard," said Sgt. First Class Julio Correa, 44, who is based at Fort Bragg, N.C., and has notified two families of deaths and assisted two others. "You see the kids screaming. You think, 'It could be my kids.' "

But typically the Army's notification officers, who bring news of the death, and its casualty assistants, who help families afterward, are picked simply because they are nearby. Their training often amounts to reading a manual and watching a video. Casualty duty is a side job. The officers and assistants are told to focus on families as long as needed, typically six weeks. Sometimes they retire or are reassigned midstream. Eric K. Schuller is a senior policy adviser for the Illinois lieutenant governor, Pat Quinn, whose office has dealt with distraught families, including the Eisenhauers and Ms. Neal.

"This had to be fixed," Mr. Schuller said. "There were so many of them over a large period of time."

Still, the casualty process has improved since the Vietnam War, when it amounted to little more than face-to-face notification of a death.

"It is dramatically different now in terms of how they respond and the number of survivor benefits," said Morton Ender, a West Point sociology professor. "They really embrace the family."

The Army acknowledges that more can be done. Mr. Harvey, the Army secretary, ordered an investigation last September to help address families' concerns.

The report, issued in January, included suggestions that the Army is planning to implement, including upgrading training materials, creating a 24-hour hot line and sending mobile casualty assistance training teams across the country.

The Army now requires commanders to telephone families within a week of a death and to cross-check casualty reports.

Congress has asked for an investigation by the Government Accountability Office.

These instances, Colonel Torgersen said, "do cause us to reflect on our processes."

She added, "In the end, however, this work is carried out by human beings and however hard we may strive, none of us are invulnerable to error on occasion."

-------

Link Here